"Personally, I try to be discreet, avoid getting too much attention when I'm in certain places or with people who could react badly."

Omar's fears are rooted in the fact that homosexuality is a criminal offence in Morocco, as it is in many other African countries. The law combines with a strongly conservative society to create a real sense of danger for members of Morocco's lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) communities.

And, as I point out in my book, the weight of Islam - Morocco is a predominantly Muslim country - adds another dimension, accentuating gay people's feelings of denial, self-loathing and guilt.

Violence and arrests

Several other interviews I conducted show how carefully people must manage their personal lives to avoid being caught. Halima, a 41-year-old bank manager, said:

"My female friend and I rent an apartment in Marrakesh, where we meet from time to time, where we can finally be together without hiding. But again, we must pay attention to the neighbours, to the doorman, to what people may say. It's something that weighs a lot on us.

|  | The criminalisation of homosexuality does not comply with Morocco's 2011 Constitution |  | |

There have been several high profile cases of homophobic violence in Morocco. In July 2015, a man was brutally beaten in the city of Fes by a mob who hurled epithets at him because he was apparently gay.

In November 2016, two teenage girls were arrested in Casablanca after kissing each other in public. They were later released, but not before the UN Human Rights Committee reacted to the story by calling on Morocco's authorities to decriminalise homosexuality.

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly echoed this call, pointing out that the criminalisation of homosexuality does not comply with Morocco's 2011 Constitution. In the constitution, Morocco pledges to "ban and combat all discrimination against anyone "on the grounds of their sex".

But such a move seems unlikely any time soon.

Instead, it's often the authorities themselves that make LGBTIQ Moroccans feel unsafe. Hassan (43), a businessman in the city of Tetuan, told me that he was "never safe from the abuse or zeal of a police officer".

However, he and others I spoke to have no intention of leaving Morocco.

I am vigilant for fear of being harassed in the street. It's a form of resistance, because I have no choice if I want to continue living in this country, a country I love, where my family lives, my friends, where I've invested.

A few open spaces

There are some spaces where gay Moroccans feel they can express themselves a little more openly. Largely, these are social networks where people can chat to others and sometimes arrange to meet discreetly in bars, clubs or bath houses.

Aicha, a 34-year-old teacher who lives in Fes, told me: "We are in a country where homosexuality is punishable by imprisonment. The way out is to meet through friends or social networks, even if it removes the spontaneity of direct contact."

Some high profile intellectuals have emerged in defense of the gay community. For instance the French-Moroccan novelist Leila Slimani has denounced the "humiliation" of gay people in Morocco. In a statement to the Huffington Post's Maghreb edition, she wrote:

"I am obviously for the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Morocco. These restrictive laws contribute to the indignity of the citizens and to their humiliation."

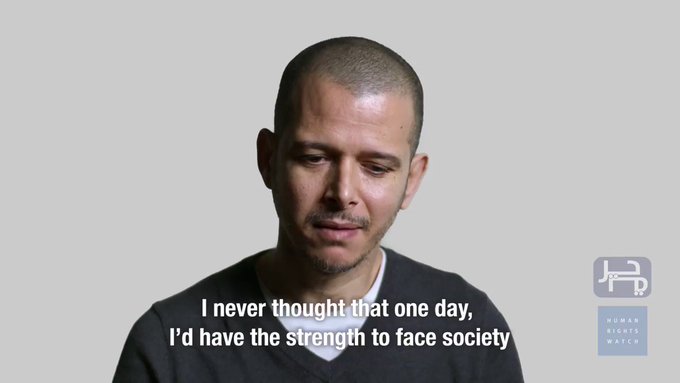

Abdellah Taia, another French-Moroccan writer, is one of the first Moroccans to come out publicly as gay. He toldThe Guardian that "there are also people who support the LGBT community in Morocco", especially human rights groups.

And the weekly Francophone magazine TelQuel used an editorial to call for the "respect of gay rights" and "equality." It stated that "Article 489 of the Penal Code is an aberration and pure archaism." This is the legislation that criminalises homosexuality.

Despite these small steps, for now social networks and internet forums are the only really safe space for gay people in Morocco. There, they can be open and even provocative about their lives and sexualities.

Read more: 'We are human and we have rights': LGBT activists speak out across the Middle East

Perhaps one day this will change. But with the country's combination of established public morality and religious values, it seems unlikely to shift any time soon.

Moha Ennaji is Professor of Linguistics, Gender, and Cultural Studies at Université Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah. He is one of Morocco's leading academics with research interests in North African culture and gender issues, language and migration.

Follow him on Twitter: @mennaji

No comments:

Post a Comment